By Andy Adams

Excerpted from “20th Century Warriors”, Ohara Publications Inc., 1971.

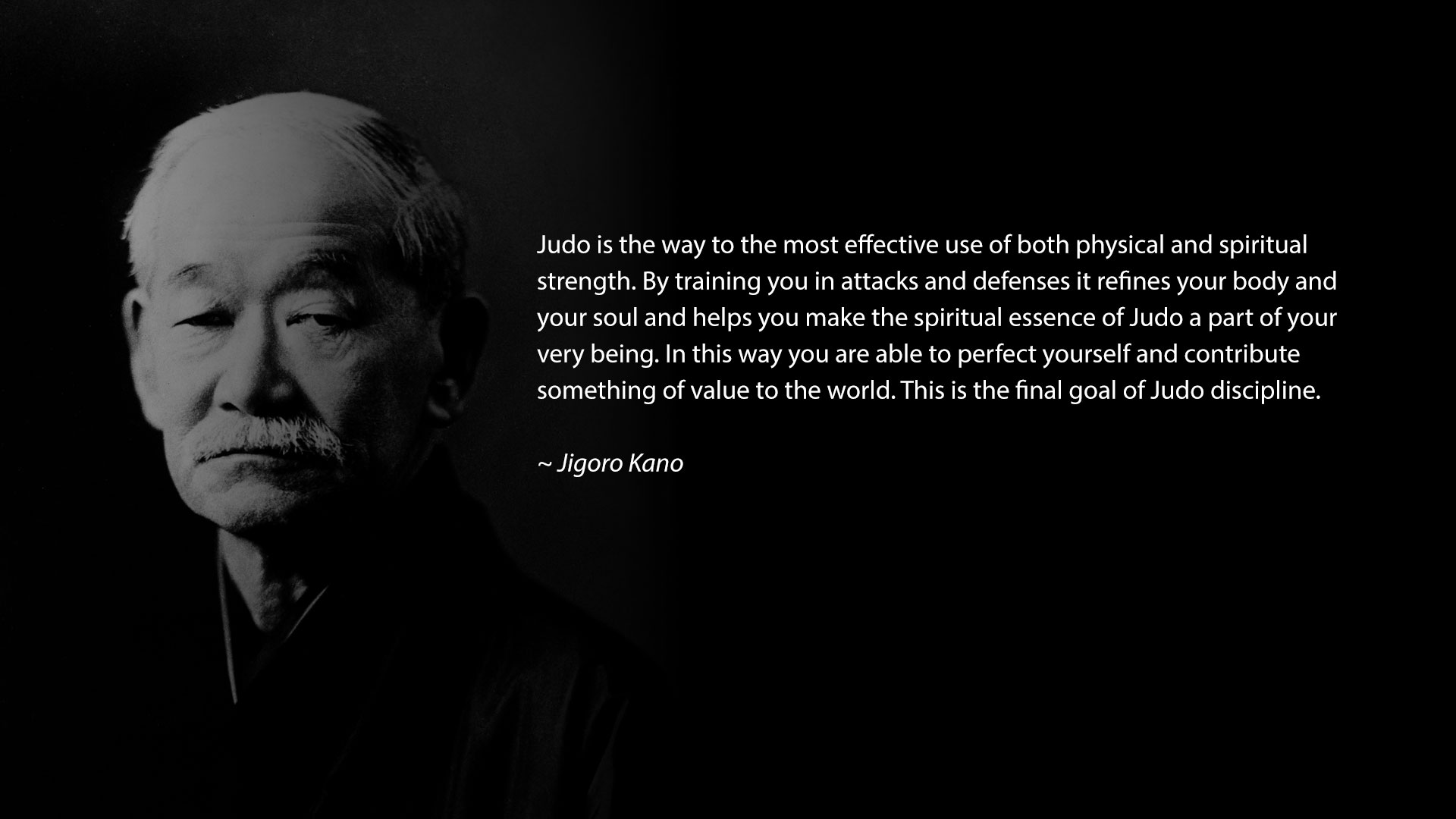

From scattered quotes taken from sources close to him, we can only glimpse Jigoro Kano, the man.

He used to take an umbrella with him every day because he didn’t like to worry about whether or not it would rain. When he returned home, he would go straight into the living room, which meant on most days I would not see my father at all.

He was very strict with us at school. I had to get up at 5 o’clock every morning and help clean the rooms and the garden. He was so proud of his legs he used to pull up his hakama (uniform pants) just to show off his big calves.

Kano was a perfectionist, a disciplinarian and a traditionalist. But at the same time, he was an innovator, an internationalist and a man of great generosity. More important, he was a famous educator and the father of modern sports in Japan. But above all, he was the founder of judo.

When Kano first saw the light of day on October 28, 1860, Japan’s feudal period was rapidly drawing to a close. He was fortunate enough to be born into a family that was reasonably well off. His grandfather had launched the family into the business of making sake in Nada, Shiga prefecture.

The third son in a family of three boys and two girls, the young Kano was physically weak in his early years. In fact, he was beaten up so often by local bullies that he resolved to strengthen himself the best way he could. It was this unrelenting drive to learn how to defend himself that eventually led to his formulation of judo.

One wonders what would have happened had he been a big brute of a man instead of the 5-foot-2-inch, 90-pound weakling he was in his teens. Jujutsu flourished in Japan during Kano’s boyhood. One might even term the mid-19th century the golden age of the art. So it was with rather anxious expectations that Kano looked forward to moving to Tokyo, where most jujutsu activity was going on.

When he was 17, his father ordered him to go to the capital on board one of the sake-carrying ships, but he insisted on traveling by land. His father relented fortunately, for the vessel broke up in stormy seas and sank. Kano started jujutsu at age 17, but his instructor, Ryuji Katagiri, believed he was too young for serious training. As a result, Katagiri gave him only a few formal exercises for study and let it go at that.

The determined young man was not about to be put off so easily, however, and finally wound up at the dojo (training hall) of Hachinosuke Fukuda, a master in the tenjin-shinyo-tyu style of jujutsu. Fukuda stressed technique over formal exercises, or kata. Although his method included explanation of the exercises, he concentrated on free-style fighting in practice sessions.

Kano’s later emphasis on randori in the teaching of judo undoubtedly found its beginnings here under Fukuda’s influence. In 1879, a year after Kano started working out at Fukuda’s dojo, the jujutsu master suddenly became ill and died. The 19-year-old Kano soon joined another branch of the tenjin-shinyo-ryu that was run by a 62-year-old instructor named Masatomo Iso.

Located in the Kanda section of Tokyo, Iso’s dojo was known for its excellence in kata. Over the next two years, Kano ate, drank and slept jujutsu. Things got so bad he even started having nightmares about the martial art, shouting jujutsu terms in his sleep and kicking out at his quilt. But the sensei (instructor) saw the student’s dedication and promise and soon made him an assistant instructor.

By the time he was 21, Kano had become a master of tenjin-shinyo-ryu jujutsu. But Iso, like Fukuda before him, soon became ill, and Kano decided to move on because he wished to study rather than teach. Kano then met Tsunetoshi Iikubo, a master of kito-ryu jujutsu, and began training at his dojo.

Even when no one else showed up, Kano would work out alone. Like Fukuda, Iikubo stressed free fighting, and he was especially skillful at teaching nage waza (throwing techniques). It was during these early jujutsu training days that Kano worked out some new throws and turned his attention toward ways to reform jujutsu.

He ran up against a 200-pound… While practicing at the tenjin-shinyo training hall, he ran up against a 200-pound bruiser named Kenkichi Fukushima. Outweighed by 100 pounds, Kano lost to the bigger man. Afterward, he wanted to beat Fukushima so badly he could taste it, so he studied everything he could get his hands on, including books on sumo techniques. Finally Kano worked out a new technique.

The next time he met his burly rival, he charged in low, lifted Fukushima onto his shoulders, whirled him around and tossed him onto the mat. He promptly dubbed his new throw kata garuma, or shoulder whirl. Other throws he developed included uki goshi (rising hip throw) and tsuri komi goshi (lift-pull hip throw).

Kano’s original idea was merely to reform jujutsu rather than found a new art. He was well aware of the shortcomings but believed that once they were weeded out, jujutsu would be beneficial to young men as a martial art, a form of physical education, and a method for training and disciplining the spirit.

Kano dedicated himself to devising a system of reformed jujutsu founded on scientific principles, integrating combat training with mental and physical education. He borrowed the katame waza (mat techniques) and atemi waza (striking techniques) of kito-ryu, holding onto those techniques that conformed to scientific principles and rejecting all others. All harmful and dangerous techniques were eliminated.

When the 22-year-old Kano took nine of his private students from the kito-ryu training hall in February 1882 and set up his own dojo in Eisho ji Temple, judo didn’t automatically spring into being. In fact, kito-ryu master Iikubo came to the temple two or three times a week to help instruct Kano’s students. So what they were getting was more jujutsu than judo training.

The transition from jujutsu to judo was made slowly but surely, but it is difficult to pinpoint the day when what that handful of students were learning was no longer jujutsu, but judo.

It might have happened the day Kano first defeated Iikubo. Until then, he had never managed to get the better of the kito-ryu stylist, but that day in randori practice, Kano blocked every move fkubo made, then called on his refined techniques to throw the jujutsu master no less than three times.

Kano explained: “Force your opponent to make his body rigid and lose his balance, and then when he is helpless, you attack.” Iikubo replied: “From now on, you teach me.” Once the Kodokan, the world judo headquarters, was firmly established in Tokyo, Kano’s thoughts turned toward spreading the art across the nation and eventually the world. The rest, as they say, is history.

This essay was written by Andy Adams and excerpted from “20th Century Warriors”, Ohara Publications Inc., 1971.

SHOP

SHOP