The Early Years of Judo in British Columbia

This text is based on an academic essay by David M. Steele, used with permission. All rights reserved.

A man named Jigoro Kano developed the art of Judo, translated as ‘the gentle way’ or ‘flexible path,’ in Japan near the end of the 19th century. As a rather frail boy of eighteen, he studied various styles of Jujitsu, ‘the gentle art.’ In 1882, a year after his graduation from Tokyo Imperial University, Kano opened a new Dojo. The newly created Kodokan, a word that translates as ‘a school for studying the way,’ began to teach a martial art of Kano’s own devising – Judo.

Judo was the embodiment of Kano’s desire to develop a style of unarmed combat with three main purposes: to train the body, to learn to defeat an opponent in combat, and to develop a proper and superior personality. It was not merely a martial art – it was also a sport and a way of life. An open-minded individual, Kano incorporated aspects of Western wrestling along with traditional Jujitsu techniques. A skeptical public soon decided to put Judo to the test by pitting this upstart new martial art against the proven, more traditional art of Jujitsu.

In a match held by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police, Kodokan Judo was matched against Totsuka-Ha Yoshin-Ryu Jujitsu; if Judo won, the Tokyo Police would immediately switch their hand-to-hand combat training from Jujitsu to Judo. Kodokan Judo won twelve of the fifteen matches and tied one more, proving itself and ensuring its continued life. In the years that followed, Judo gained in popularity and began to spread. By 1889, Kano, an internationalist and dedicated teacher, decided that the time had come for Judo to spread out from the islands of Japan. He took his first of many trips overseas to bring his new creation to Europe and the United States. Some years later, Judo found its way to the west coast of Canada.

In 1923, Steve Sasaki decided something had to be done about Judo in British Columbia. He had grown disgusted with the Judo versus wrestling matches in vogue at the time, seeing them as nothing more than fixed contests. Sasaki had started Judo in Japan at age twelve and was awarded his first-degree black belt, the rank of Shodan, at age seventeen. Determined to promote proper Kodokan Judo in the city of Vancouver, Sasaki spent a year conducting meetings and canvassing the local Japanese Canadian community in order to gauge interest and garner support. Due to his efforts, the first recorded Judo Dojo in British Columbia opened its doors in 1924.

The club’s beginning was, to say the least, inauspicious. The Dojo itself, called the Tai-Iku Dojo, was actually the high-ceilinged living room of a Mr. Kanzo Ui, one of the major financial supporters of the new club. Other benefactors supplied mats and such, but most of the costs for the Dojo came out of Sasaki’s own pocket. This initiated a kind of trend whereby many early Judo teachers, called Sensei, spent their own money in order to teach Judo to others. One of the major financial contributor’s to Canada’s first Judo club was the infamous Etsuji Morii, a rather shady Vancouver businessman who became interested in Judo. Morii was once described as “the eminence grise of the business and gambling world of Powell Street … at once hated, feared and respected … a prominent figure in the pre-war community structure.”

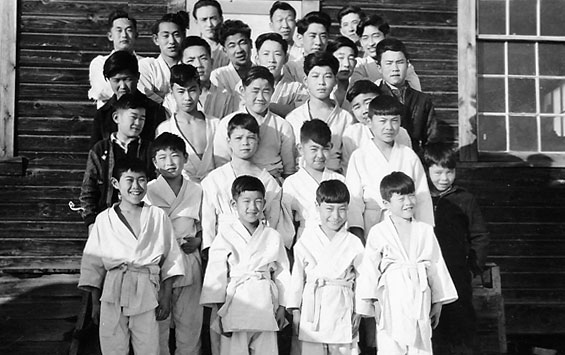

The new Judo club was quite successful, and Sasaki’s Dojo soon outgrew its colourful but humble beginnings and moved to Vancouver’s Dunlevy Street in 1925. Sasaki’s early students included both first- and second-generation Japanese Canadians; as these new students gained sufficient training, they began to take their learning and share it with others. By the second half of the 1920s Judo had begun to spread across British Columbia.

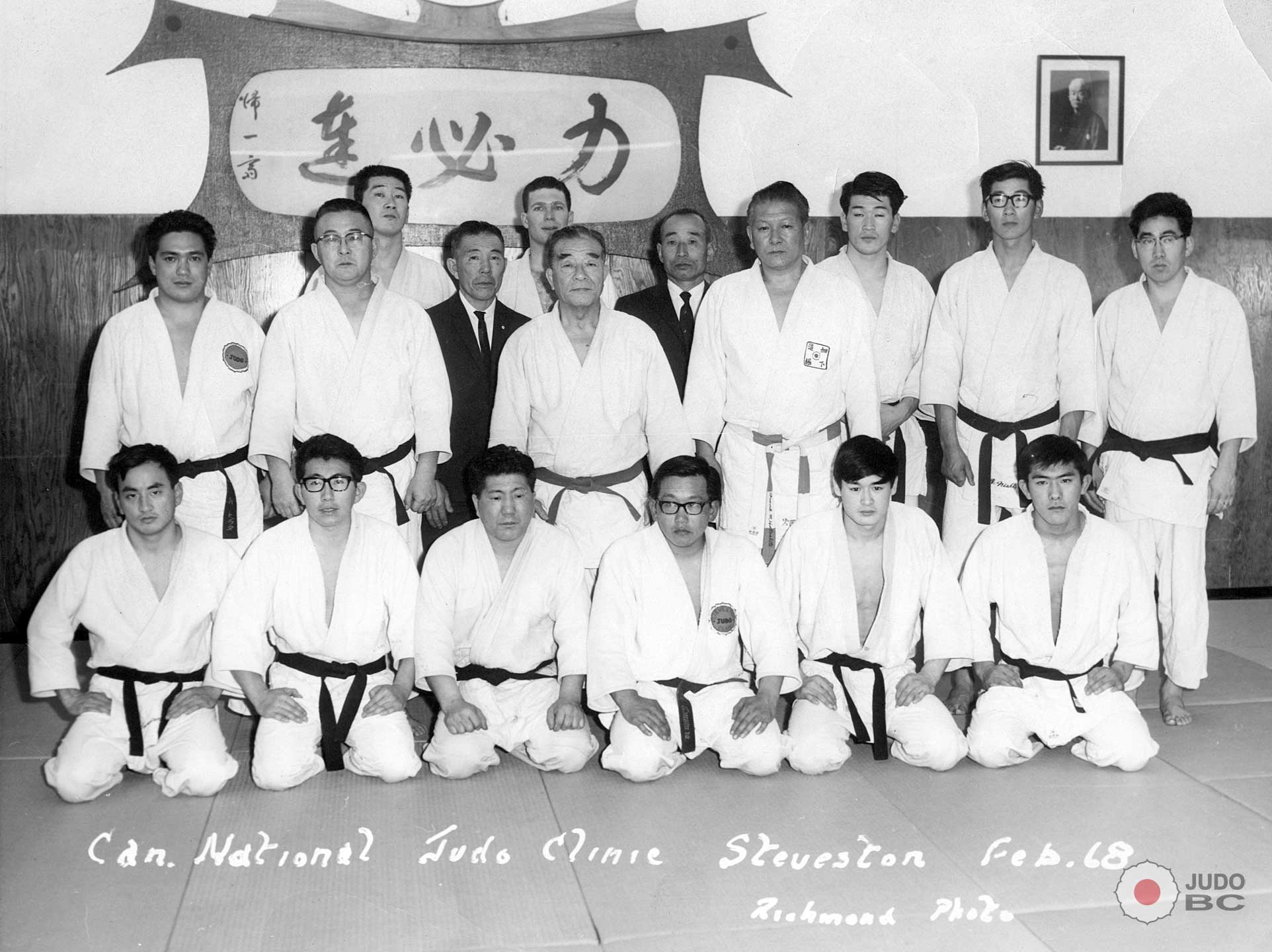

Many of Sasaki’s students went on to open other clubs in B.C. and received a great deal of help from their former Sensei in this regard. In 1926, Tomoaki ‘Tom’ Doi and Takeshi Yamamoto started a club in Steveston. They quickly turned to the generosity of the Tai-Iku Dojo. Although busy himself, Sasaki visited Steveston twice each week; in fact, the Steveston Dojo eventually became a branch of the Vancouver Dojo. Like Sasaki, Doi ran the Steveston club on a non-profit basis, asking for help from the Japanese Canadian community and even paying expenses himself when needed. More of Sasaki’s friends and students started opening their own clubs elsewhere in the province. Sasaki himself often personally aided in teaching at these new clubs, or – when this was not possible – convinced his assistants to do so. These clubs were often founded in Buddhist churches or Japanese language schools, central gathering spots for B.C.’s Japanese Canadian community. Perhaps Sasaki was, as some have commented, “simply a man of his times, as amateur athletics directed towards the working class were just beginning to percolate through Canada.” However, as the vast majority of Sasaki’s students were Japanese Canadian, it is perhaps more accurate to describe him as a community or cultural activist. In any case, from 1924 to 1932, many young Japanese Canadian men and boys began to learn Judo.

Judo training was often done on improvised mats in what were sometimes poor physical conditions for the sport and martial art. Tournaments were held between clubs, and the Judoka – the Judo students – trained hard in order to best represent their Dojo. Many American Judo clubs in the Pacific North-West participated in these tournaments and likewise invited Canadian Judoka to compete south of the border. Through the efforts of Sasaki and his students, Judo began to flourish in many Japanese Canadian communities in British Columbia. After 1932, this growing sport would experience a boost in popularity from two different sources.

In the early 30s, a commissioner from the local Vancouver R.C.M.P. detachment attended a February Judo tournament in order to observe the hand-to-hand combat aspect of Judo. Steve Sasaki’s display of the martial art made quite an impression on the R.C.M.P. representative. Soon afterwards, the commissioner contacted Ottawa and requested permission to replace boxing and wrestling training with Judo. However, the R.C.M.P. decided that Sasaki would have to demonstrate the effectiveness of Judo against the local police boxing and wrestling champions. Sasaki, in incredible shape and holding a third-degree black belt at the time, defeated both the boxing expert and the local Mountie wrestling champ. About two weeks later, the Vancouver R.C.M.P. detachment received orders from Ottawa to put Judo instruction among their regular courses, while boxing and wrestling became options. A short time after that, Sasaki opened a Judo Dojo located at the Heather Street Barracks. Eleven officers began training in Judo under Sasaki, with practices held twice each week. In 1934, eleven officers of the R.C.M.P. were awarded the rank of shodan, first-degree black belts – one of the earliest serious involvements of non-Japanese Canadians in Judo.

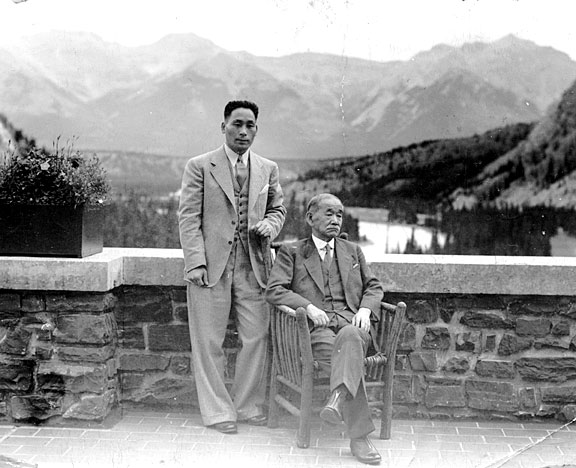

In 1936, another event substantially affected Judo in British Columbia. Jigoro Kano, Judo’s creator, visited Canada for the first time. Returning from the Olympics in Los Angeles, Kano stopped in Vancouver on 17 August 1932 to see the first Canadian Dojo devoted to Kodokan Judo. At the time of Kano’s arrival, Sasaki was in Tokyo training under Kyuzo Mifune, a diminutive Judoka of very high rank who had even competed before the Emperor Hirohito. Because of this,

Yoshitaka Mori of the Vernon Dojo had the honour of meeting Kano at the passenger docks. When Kano returned to Vancouver in 1936, however, Sasaki was there to meet him. During this eventful visit, Kano did a great honour to the young Tai-Iku Dojo by renaming it the Kidokan, or ‘house of intrinsic energy.’ He also asked Sasaki to accompany him across North America and Europe in order to help promote Judo. During this trip, Kano told Sasaki how it was important to spread Judo across Canada. This evidently had a great effect on Sasaki, for when he returned to B.C., he made several changes to the Kidokan. He had a dormitory built for the Nisei (second-generation Japanese Canadian) members of the club who lived outside the region. He also developed conversational English classes to help improve the employability of members whose English was weak. In 1938, returning from international Olympic committee meetings in Cairo, Jigoro Kano stopped in Vancouver one final time. A group of young boys from the Kitsilano Judo club assembled at the docks to meet Kano and Sasaki. Unfortunately, this was to be Kano’s last visit to Canada; a painful loss to Judo worldwide, Jigoro Kano passed away on the voyage back to Japan.

Though it survived Kano’s passing, Judo in British Columbia nearly disappeared following an even greater tragedy. British Columbia had never had a shortage of anti-Japanese sentiment; however, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, public sentiment gave way to a cry for action. Nearly two months later, the Canadian government created a protected area 100 miles wide along the coast of British Columbia which was deemed off-limits to all people of Japanese racial descent. Japanese Canadians west of the Rockies were to be relocated in camps further east in Western and Central Canada. The Judo clubs were perforce shut down as the teachers and students were removed from the protected area.

Some of BC.’s Judo instructors, influential community leaders according to a 1942 intelligence report, were among the first to be arrested. This created some interesting confrontations between the police and B.C. Judoka. The Nakashima Judo Club still tells about an incident that took place during these times when Yasumatsu Nakashima, the founder of the club, was about to unload his fish at the dock. He was met by three police officers who attempted to use force rather than reason when they came to seize his boat; they were all rewarded with free swims. Fortunately, this scene was relatively rare; although the Judoka were more than capable of resisting physically, most complied with the demands of their government. Businesses that also housed Judo Dojos were seized and sold as Judoka boarded trains and left for an unknown fate east of the Rockies.

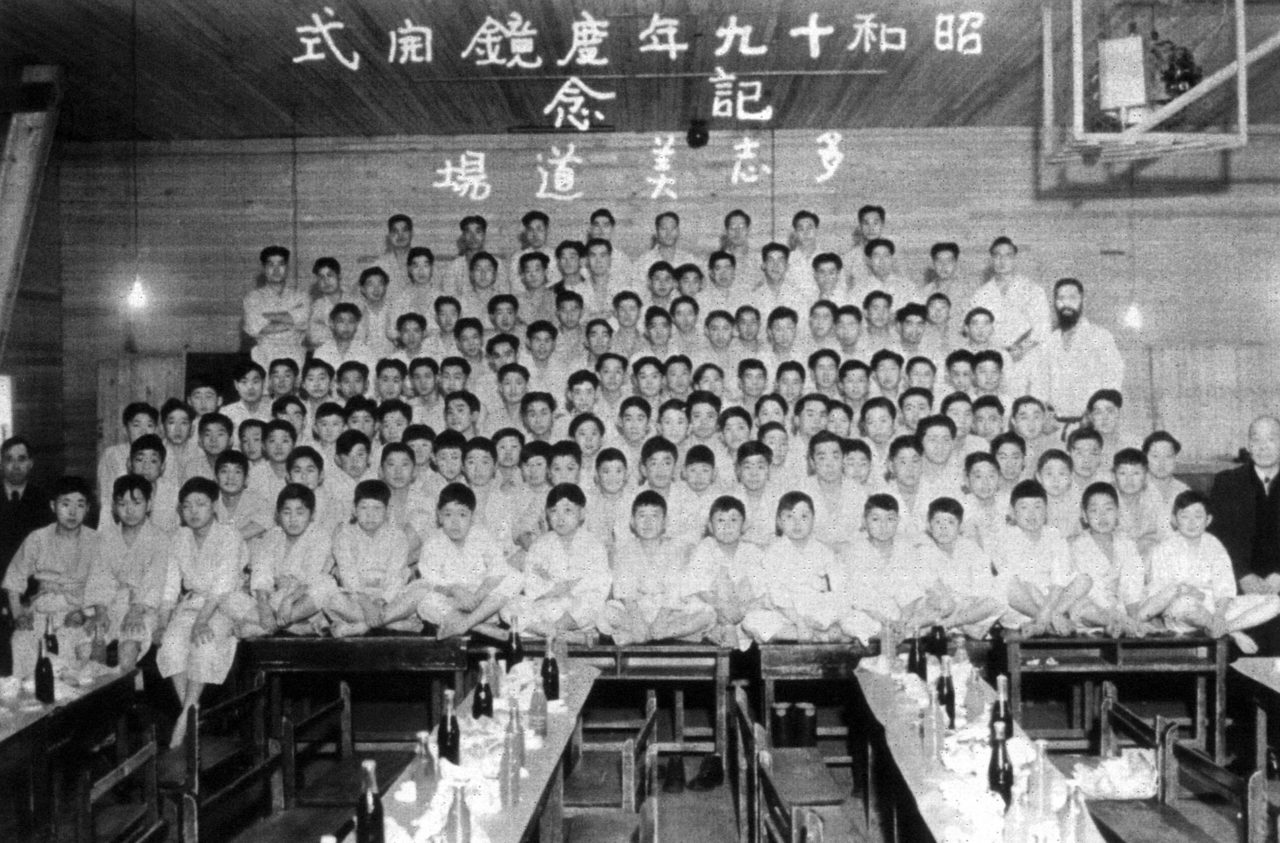

The wartime relocation could well have resulted in a permanent end to Judo in British Columbia. However, due to the efforts of Sasaki and his students, as well as to the close relationship Sasaki had forged with the R.C.M.P., Judo did not perish in the internment camps. Although homes, boats, radios, cars, and businesses were seized and sold to fund the relocation process, Judo survived. In the Tashme camp, a family detention camp twenty kilometers north of Hope, Steve Sasaki and Atsumu Kamino continued to teach Judo. Their students were primarily young boys, as men between the ages of 18 and 45 were often sent to work camps to be used as essentially slave labour. With around 2500 internees, Tashme held the largest concentration of Judoka among the three internment camps. Sasaki’s affiliation with the R.C.M.P. served him well in this regard, as the only contacts the internees had with the outside world were R.C.M.P. officers, B.C. Security Commission representatives, and the camp store operator. When Sasaki asked the B.C. Security Commission to allow Judoka to join him at the camp, his request was granted. Although many of the former Judo practitioners were unable to train while labouring elsewhere, Judo was being spread among a new generation of Japanese Canadians. This teaching of Judo was also taking place in the Popoff camp as well as the Angler P.O.W. camp. Genichiro Nakahara of the Chemainus Dojo instructed at Popoff, while Masato Ishibashi and Kameo Kawaguchi taught Judo at the Angler camp.

By the time the restriction on Japanese Canadians in B.C. was lifted in 1949, Judo had already spread to many Canadian provinces through forced relocation and voluntary resettlement. The sheer number of Judoka who relocated to Ontario and Quebec caused a definite shift in the eventual organizational structure of Judo in Canada, a shift that saw B.C.’s monopoly of the teaching and practice of Judo come to an end.

Before the abolishment of the restricted area in 1949, the only B.C. Dojo still in operation was the Vernon Dojo, established in 1944 by Yoshitaka Mori; martial arts were still banned at this time in many places, and Japanese Canadians required a special police permit to meet in groups. Mr. Mori was the first to obtain such a permit for Judo. It was not until the early 50s that Judo returned to the coast of British Columbia. As the Japanese Canadian fishermen and their families returned to coastal B.C., so too returned some of Judo’s early practitioners. Following his stay at Tashme, Steve Sasaki moved to Ashcroft in 1951. It is well known that he taught Judo there and eventually opened a Dojo, although the exact inception date of the club is unclear. The Vancouver Dojo is therefore considered the first coastal Judo club to officially reopen its doors. On the corner of Cordova and Princess, in the old Ukrainian Hall, Tomoaki Doi, Yonekazu Sakai, and Graham Hall – the first Caucasian promoted to black-belt after the war, and the very first Canadian promoted from white belt directly to black – reopened the Dojo. The following year, Sasaki met with Doi to discuss the establishment of a new Judo Dojo in Steveston to replace the one that was abandoned. They called together many the former pre-war practitioners and, as a group, decided to form a new club. As most of the Judoka had no money, there was some difficulty acquiring funding; an interest-free loan from the Japanese Fishermen’s Benevolent Society allowed the Dojo to buy mats and open for business. The instructors were all volunteers, and the club complement at its rebirth, including children and adults, was around 80 members. Other clubs soon followed, and Judo was once again alive on the west coast. Kano’s advice to Sasaki had taken root at last; Judo had spread across Canada and, thanks to the efforts of Sasaki and his students, and once more returned to its Canadian roots on the shores of British Columbia.

Judo BC 50th Anniversary

Judo BC celebrated 50 years, as a registered society on June 6, 2014 at the Executive Airport Plaza Hotel & Conference Centre in Richmond, BC. The evening’s master of ceremonies was Al Sakai who spoke to the importance of the people who give Judo BC its identity and character. During the course of the night, guests were treated to a buffet dinner, slide show, trivia contest, storytelling and more than a few good laughs. Read more…

SHOP

SHOP